I started my bike and immediately noticed that the charging system wasn't working. I could tell because I had an ammeter on board and it was reading steady discharge. A little scraping with a pocket knife removed some corrosion on a connector and a minute later I was on the road.

I've written about this before, but this time I'll expand on it a little.

The electrical energy coursing though your motorcycle has both flow and pressure. It flows, thus has current which is measured in amperes, or amps for short. It also has pressure, which is really just electrical strain between one place in the circuit and another, the result of accumulated electricity, measured in volts. An amp meter, or ammeter, shows electricity working, while a voltmeter shows only its before- or after- effects. 1 One is active, the other is passive. For this reason, an ammeter makes a better monitor of the charging system than does a voltmeter. 2, 3, 4

Picture water flowing out of a faucet into a bucket. As a moving thing, it is gauged intuitively; changes in its flow show up instantly. On the other hand, the water's height in the bucket changes slowly; it's not as readily noticeable.

The ammeter was once common. In earlier days electrical systems were less reliable and monitoring them was crucial. By the early 1970s however, ammeters had already all but disappeared and original equipment ammeter use is pretty rare today. Despite this rarity, the ammeter is as useful today as ever. And it is fairly inexpensive and easy to install.

Pick an ammeter that has a small range, under 20 amps if possible; 10-15 is ideal. The needle on a 20-amp or larger automotive instrument will barely wiggle on a motorcycle, and since wiggle is what an ammeter is all about, it will be nearly useless. 5

Wiggle? The ammeter is a compensation monitor. It is constantly recording losses and their compensations. These appear as equal needle swings in opposite directions, always centered on zero. As the bike is ridden, the needle's swing left and right starts out large but gradually decreases until it gets very small, indicating that the battery is near maximum charge after some time riding the bike. At a stop the needle will dip a certain amount below zero when you put the brake on. Then, accelerating from the stop, the needle will swing an equal amount the opposite way above zero, showing the compensation. As the bike is steadily ridden this swing will again gradually get smaller until it is merely quivering over zero. As long as the engine is running, the ammeter needle's wiggle never completely stops.

This is a scenario that many find unintuitive, and is probably why ammeters fell out of favor. However, once you have spent some time observing it, it will become more intuitive. You'll find the ammeter faithfully represents the interplay between battery and alternator, offering a moment-by-moment picture of the health of the charging system. You will probably be surprised that the battery loses so much charge upon starting the vehicle, and equally amazed that the bike replenishes that lost energy so quickly at the beginning of the ride. Each loss, as it is introduced and then compensated, will display on the meter. The turnsignals, for example, will increase the wiggle of the ammeter in sync with the flashes.

It is normal for the ammeter to occasionally peg. This doesn't hurt the meter as it is electromagnetically driven, not mechanically like a pressure gauge. It may peg when the engine is electric started, and once in a while at a stop if you rev the engine from idle. This is normal.

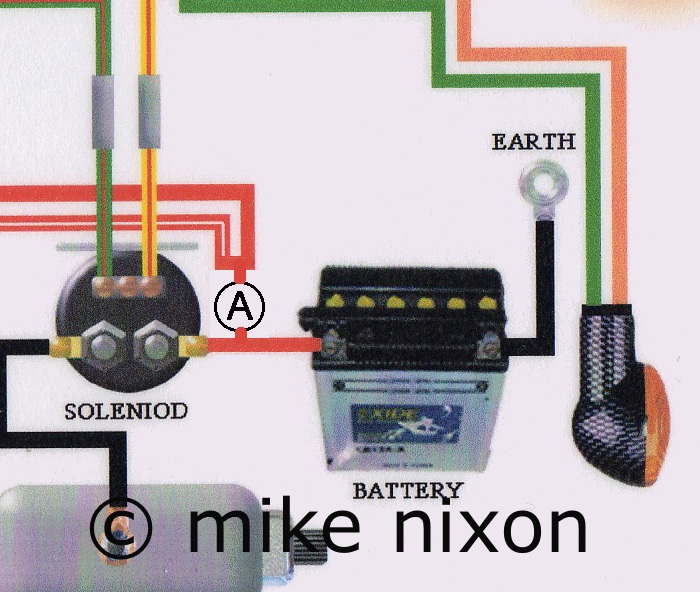

On a Honda, an ammeter is ridiculously easy to install. You just find the highest current point in the charging system, which is the red wire with a white stripe. You then break into this wire as near as possible to the rectifier, which means separating the joint between the red/white and plain red wires. Wire the ammeter there. Use heavy gauge wiring (16 ga. minimum) and route it carefully as this will be a high current path.

Notes:

1. One ampere is a certain quantity of electrons (the invisible bits that actually do the moving) that pass by a given spot in the circuit in a second. Specifically, one coulomb per second, if I remember correctly.

2. Technically, an ammeter is really a voltmeter with a shunt added that measures voltage drop and indicates it based on Ohm's Law as amps. In the end though they're very different instruments.

3. Think about this for a minute. What is the output from the battery into a horn or ignition system measured in? Amps, of course. A standard method. Why then, when considering the movement of electricity *into* the battery instead of out of it, do people want suddenly to switch to volts? Is that logical?

4. Although measuring both is good practice, and is shown in Honda's earliest service manuals. It's helpful because the much less common malady of over-charging is more easily confirmed with a voltmeter.

5. The ammeters for sale on my website are new replacement parts for jeeps and construction equipment. I chose them for their ideal measuring range.